Twenty years ago, stomach ulcers in horses were not a commonly reported problem and veterinary texts listed them only as an infrequent finding in sick foals. Today, they are reported to occur in anywhere between 60 and 90% of standardbred racehorses and 50 to 60% of show ponies, stabled yearlings, eventing and dressage horses. The only group of adult horses free of ulcers are those on pasture 24 hours a day.

Pastured horses have a very different diet to stabled horses – and diet has been shown to contribute to ulcers. Under natural conditions, horses graze for around 16 hours per day. The stomach has adapted to a constant intake of grass by constantly secreting acid (for around 45 minutes per hour). The acid is buffered by saliva, which is produced during chewing and has a very high content of bicarbonate and mucus. The number of chewing movements and the amount of saliva produced varies with the type of feed. One kilogram of hay requires over 3000 chewing movements and results in the production of over four litres of saliva. One kilogram of grain requires only one third as much chewing and yields only two litres of saliva. The sign of an acid stomach is chewing of bedding, wood etc – the chewing process stimulates the flow of saliva, which in turn lowers stomach acid levels and the horse feels more comfortable – a bit like chewing an antacid tablet.

Stabled horses spend an average of four hours a day eating – compared to 16 hours for pastured horses. When chewing time and hence saliva production are reduced, stomach acid levels rise, increasing the risk of ulcers. High acid levels are a result of modern feeding practices: the amount of roughage, feeding frequency and type of feed have profound effects on stomach acidity. If the stomach sits empty for a prolonged period, the acid is not buffered by the food and saliva and the stomach will empty less frequently, allowing the acid fluid to remain in contact with the lining.

When feed is eaten rapidly, less saliva is produced and the sudden flow of a large volume of feed into the stomach causes a rapid increase in acid secretion. Both grains and pelleted feeds have been associated with increased risk. High grain diets favour bacterial growth and fermentation in the stomach. There is an increase in the number of bacteria that produce lactic acid and gas. Acid secretion increases in response to pelleted feed because pellets are eaten rapidly. Both weanling and adult horses consume pellets faster than they eat traditional grain diets.

Simply changing from pasture to hay and confining a horse to a stall can cause ulcers. Because hay is drier and coarser than grass, it can damage the lining of the stomach. Soaking hay for 6 hours will soften it and also reduce dust and airborne particles that irritate the respiratory system. In addition, any alterations in intestinal function may also be associated with stomach ulcers. Insufficient blood flow due to worms can cause death of gut lining cells, resulting in slowing ulcer healing.

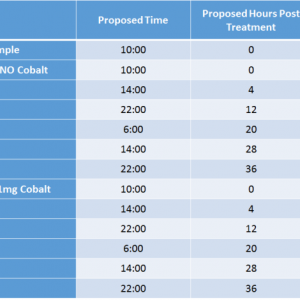

The most reliable way to produce ulcers in a horse is to provide insufficient roughage or to fast them. Multiple studies have demonstrated that periods as short as 12 hours without feed can result in low grade stomach irritation. Even beginning an exercise program results in more acid secretion by the stomach – making the provision of adequate roughage even more critical for the standardbred entering training.

Phenylbutazone or other anti-inflammatory drugs can also cause ulcers. The risk increases with long term use but can occur even after a single high dose. Phenylbutazone (bute) especially has an extremely low margin of safety and should only be used under veterinary supervision. A high salt intake can irritate or worsen pre-existing ulcers. To avoid excessive irritation, ensure that electrolyte intake matches need and give the daily dose with food.

Signs of stomach ulcers include poor performance, loss of appetite, poor condition and mild colic. With the exception of mild colic, these symptoms can also be found in horses with a developing lameness, subclinical tying-up, a gut upset, electrolyte imbalances, sand ingestion and enteroliths. However, loss of appetite for grain, signs of mild pain after eating, teeth grinding, salivation and belching are characteristic signs of stomach ulcers. While horses with a nervous temperament are thought to be more prone to ulcers, it is more likely that discomfort from stomach ulcers makes horses agitated and restless.

Horses with severe ulcerations and clinical symptom require treatment for at least 3 weeks. Around 20% of horses do not respond in that time and may need a different pharmaceutical or a spell. Horses with ulcers have notoriously poor appetites and may not have been eating all their medication if it was in the feed. If dosed with it, poor technique could also lead to loss of some medication. There is also a widespread problem with horses being given inadequate doses or not being dosed frequently enough, in attempts to save on the cost.

As few as 3% of moderate to severe ulcers heal without treatment in horses kept under conditions that predispose to ulcers. The only treatment that is 100% effective is to turn the horse out on pasture. Bear in mind also that the combination of poor appetite and alterations in gut pH, have negative effects that drugs cannot correct and supportive therapies, such as probiotics, should be considered. Even with improved appetite and weight gain, there can be a persistent mild dehydration, which can respond to combined probiotic/amino acid/electrolyte. Gamma oryzanol has been shown experimentally to have a protective effect on ulcer formation in several species, particularly ulcers induced by stress or fasting.

For less severe symptoms, and after the initial drug treatment, there are far less expensive therapies for continued treatment and prevention. Good results have been obtained with probiotics, gamma oryzanol, fermentation products, yeasts and digestive enzymes. These actives can be very effective in improving appetite, correcting diarrhoea and promoting weight gain. Some horses with ulcer-like symptoms that do not respond to anti-ulcer supplements respond extremely well to probiotics. In addition, under the guidance of your veterinarian, consider a special worming program for immature worm stages and for tapeworms.

In addition, not all gut symptoms are caused by ulcers and it is essential to have a veterinary assessment to rule out other causes of reduced appetite, weight loss and discomfort. Following a clinical and/or endoscopic examination, the various ulcer treatment options can be assessed. Because of the major drawbacks of treatment – cost, contravention of the Rules of Racing and recurrence of ulcers once treatment stops – long-term prevention with gamma oryzanol or another protectant, is advisable. Preventatives and treatments include good quality aloe vera juice, chlorophyll, gelatin kaolin, apple pectin, aluminum and calcium-based antacids, however, long-term use of compounds containing aluminium has been associated with toxicity.

The following feeding management practices can reduce the risk of ulcer formation:

- Avoid prolonged periods of fasting – ulcers have been shown to develop within 10-12 hours when horses have no access to feed – ensure roughage available at all times

- Feed on the ground – horses chew and swallow more efficiently when their heads are down and the throat extended. Feeding above the ground also results in abnormal movement of the lower jaw and unnatural patterns of chewing and teeth wear.

- Feed frequent small meals – optimum is 4 times a day and not more than 2 kg of grain per feed.

- Use steam-extruded grains and feeds which have been processed in such a way that eating is slower, resulting in more chewing, increased saliva production and higher saliva bicarbonate levels.

- Deworm regularly with the correct compound.

- Include probiotics and protectants such as gamma oryzanol in the daily diet.

By Dr. Jenny Stewart BVSc BSc PhD MRCVS

Equine veterinarian and Consultant Nutritionist